The Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitri Rogozin and another passenger – a deputy in the Russian Duma - feature the EU black list with overfly interdiction.

When specifically asked by Bucharest if Rogozin was onboard the aircraft which asked permission to enter the Romanian airspace, the Russian commander lied and said : "No".

Trough the diversion Rogozin created, Moscow planned two important operations:

1. Checking and measuring Romania’s reaction as an EU country, related to the enforcement of sanctions adopted in Brussels. Romania responded correctly from an institutional point of view, even if it was forced to accept Rogozin's aircraft into the Romanian airspace for about 30 minutes.

2. The clandestine takeover of the files from Tiraspol with the signatures related to the so called independence of Transistrai and its annexation to Russia. Making use of his governmental capacity, Rogozin snatched the files and transported them in his motorcade. Some of the files were captured by the secret services in Chisinau right from Rogozin's special plane.

The Russian Deputy Prime |Minister left to Moscow with an airliner.

Saturday, May 17, 2014

Here are two very instructive graphs. The first is a graph of the annual changes in the UK Retail Price Index for the period 1948-2013 - courtesy of the Guardian.

You can see the amazing period that I remember well as a teenager in the early to mid 70s, when inflation exceeded 25% per year. Margaret Thatcher put a stop to that with Monetarist policies that severely restricted the growth in the money supply by dramatically increasing the rate at which the Bank of England lent to the Commercial Banks. It was the time when everyone talked about M3 and M4. Controlling the money supply was the key to controlling inflation.

The second graph shows how various prices have increased for the period 1956 to 2010 - thanks to Alan Dick's number crunching. It shows how, while the retail price index (RPI) and the amount of cash in circulation (as measured by the number of on-month Treasury Bills - T Bills) were both kept under control from the early 1980s onward, two other measures have gone through the roof.

The first is the Nationwide House Price Index. As Alan Dick says, In January 1956, the average house price was £1,937, but this had increased to £167,364 by the end of september 2010. Inflation alone would have increased the value to £38,486.

That's not bad, and the returns were particulalry impressive during the massive property boom from 1997 to 2007. But the really big returns were to be found by investing in shares. The same amount of money invested in shares would be work £973,030 by September 2010. And I suspect that there are a whole pile of other areas where investing in the financial sector will have produced bumper yields for this period.

I get the impression that, back in the 1970s, the financial sector hadn't yet worked out how to pump large amounts of newly created money/credit/debt into the economy without producing inflation. But with the stimulus of Thatcher's monetarist policies, from the 80s onward, they discovered that by concentrating money creation on (a) the housing market, and (b) the financial markets, and in particular the stock market, they could reap fantastic amounts of money without causing too much inflation for the rest of us. Very crafty.

Since the only remit for the Central Banks was to keep inflation within bounds, and ideally at around 2-3%, this was all fine. The Banks were given the green light for generating colossal amounts of fresh money. The only thing that they should avoid doing was to let any of the general public get their hands on it. Yes, lend it to people to buy houses. That's ok, because most of them won't be able to spend the money because they actually need the house as a place to live. Sure, there will be a small percentage of relatively wealthy people, who will be able to make an absolute packet by buying houses to rent out, or by selling up and buying a nice farmhouse in the south of France. But those few people will not be able to cause serious inflation on their own.

Wouldn't things have been much better if the money creation process had been in the hands of an authority that had the interests of the general public at heart?

Friday, May 16, 2014

Christine Lagarde's concerns about eurozone deflation and the Ukraine crisis are shared by many investors, according to Bloomberg's latest survey.

Christine Lagarde's concerns about eurozone deflation and the Ukraine crisis are shared by many investors, according to Bloomberg's latest survey.

Its Global Investors poll found "overwhelming concern" about deflation in the euro zone. About three-quarters of them say it’s a greater threat to the region than inflation.

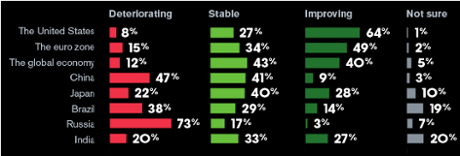

They are also less optimism about the global economy. Here's a flavour:

Forty percent of respondents in the survey of Bloomberg customers say the global economy is improving, another 43 percent say it’s stable, and only 12 percent say it’s deteriorating.Still, the enthusiasm has cooled: 59 percent thought the economy was improving in the last edition of the poll, in January; that was the highest reading since the world emerged from recession in 2009.

The survey also found that most investors fear the Russian economy is deteriorating, while half believe the eurozone is perking up.

More than seven in 10 of those polled say Russia’s economy is weakening, and 45% recommend selling Russian assets in light of the conflict in Ukraine

Bloomberg also found that French president Francois Hollande was the most unpopular politician, with just 11% saying they're optimistic about his policies. Putin followed close behind with an optimism vote of 15%, while Greece's Antonis Samaras secured 37%.

The most popular leader is Germany’s Angela Merkel, about whom 76 percent of respondents were optimistic.

Thursday, May 15, 2014

When a horse breaks a leg they shoot it to put it out of it`s misery. Well the EU is

now like a horse with more than one broken leg, it is time to put it out of it`s misery.

This will benefit all concerned, especially the soft under belly of the Eurozone. and

more importantly the Uk and Eastern Europe.

FLORENCE, ITALY — European Union countries are struggling to agree on the approach to take on the crisis in Ukraine, despite broad condemnation of the actions of Russia, outgoing European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso said on Friday.

Barroso, who is due to step down after 10 years in office, said the Ukraine crisis was the biggest threat to security in Europe since the fall of the Berlin Wall with greater potential for destabilization than the Balkan wars of the 1990s.

He said European countries had decided to support Ukraine and to show that Russia's actions had to have consequences but he said settling on a united response was “still a work in progress” given different views by EU member states.

“And this, let's be honest, this is the issue,” he said.

EU countries have moved slowly towards agreeing a tougher line on applying sanctions against Russian companies but Barroso's comments underline how difficult it will be to reach any more far-reaching agreement.

Differences within the 28-member bloc, much of which depends on Russian gas supplies, have stood in the way of agreement on toughening the limited sanctions against members of the Russian elite. Germany, Europe's most powerful economy, is urging more room for diplomacy while others, including Britain and France pushing for tougher action.

German growth could be reduced by up to 0.9 percentage points this year if the EU imposes tougher sanctions, a German magazine reported, citing a European Commission study.

Barroso, who said he had met Russian President Vladimir Putin more than 20 times during his time in office and had spoken frequently with him during the crisis, said Putin's ambition to strengthen ties with some of the former Soviet Union states to create a new Eurasian Union was behind the crisis.

“He wants to build on that and enlarge it to become a Eurasian Union, a kind of a pole of power opposed to the European Union, unfortunately,” he said.

Barroso also defended the record of the Commission in the financial crisis which took the euro zone to the brink of collapse in late 2011, saying it had taken the right decisions in defending the stability of the single currency.

“The existential crisis of the euro, I think we can say is solved now,” he said.

“No complacency, some problems remain and we know the difficulties that exist mainly in social terms but the reality is that those observers, those analysts in Europe and outside who were predicting the Greek exit, they were predicting the implosion of the euro, they were completely wrong. They are the ones who have to apologize.”

Wednesday, May 14, 2014

Europe's banks need a fundamental restructuring to sort out the mess from the 2008 financial crisis and enable them to fund the growth that the eurozone and British economies so desperately need, a former senior aide to European Commission president José Manuel Barroso has claimed.

Philippe Legrain, who in February ended a three-year stint as Mr Barroso’s independent economic adviser, believes that a banking shake-up is essential as the first part of a three-pronged strategy to get Europe back on track.

“Europe needs to restructure its banking system,” he said in an interview with The Telegraph. “The Americans have been much more vigorous in that than we have.

“There has been a belief that it’s best to try to preserve existing banks and exercise regulatory forbearance rather than force them to face up to their losses, sorting viable banks from unviable ones, recapitalising viable ones and closing down the unviable – the usual standard policy for dealing with a banking crisis.

“The rule book has been broken here in Europe and the result is that we have a zombie banking system that keeps alive zombie companies that should go bust, while failing to extend credit to promising new companies that could deliver future growth.

Tuesday, May 13, 2014

In Warsaw there was a bit of a May

Day party in a park next to an ornamental lake: the president planting a tree,

concerts and marching bands, and families sitting on the grass having picnics.

In Warsaw there was a bit of a May

Day party in a park next to an ornamental lake: the president planting a tree,

concerts and marching bands, and families sitting on the grass having picnics.

May 1 was 10 years to the day since Poland joined the EU - along with seven

other former communist countries from Central and Eastern Europe. Big Bang enlargement they called it. And for many observers it's been one of

the biggest success stories in the EU's history - bringing the division between

East and West in Europe to an end.

Sure, there have been some economic struggles, and some difficult

transitions. Institutions in Brussels, including the European Parliament, can

seem as remote as ever.

But much of Eastern Europe is unrecognisable from the region that became part

of the EU a decade ago.

It's not all down to EU membership, but there's no question that it has

helped.

"I think (we) used this time correctly because it was not always an easy

time," argues former President Alexander Kwasniewski, who was at the helm when

Poland joined.

"There was the financial crisis," he adds, "and now Ukraine…"

The crisis in Ukraine has been a reminder for many eastern EU member states

of what they gained when they joined both the EU and Nato - a greater sense of

economic and political stability.

"People are concerned about what's happening in Ukraine," says the political

analyst Konstanty Gebert.

Unlike countries further west, this is happening on their doorstep.

"We in Poland who have always been considered somewhat paranoid and

untrustworthy with our Russia obsession inside the EU," he argues, "have the

unhappy feeling of having been right".

A sobering thought on this tenth anniversary.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)