Public confidence in the European Union has fallen to historically low levels in the six biggest EU countries, raising fundamental questions about its democratic legitimacy more than three years into the union's worst ever crisis, new data shows.

Public confidence in the European Union has fallen to historically low levels in the six biggest EU countries, raising fundamental questions about its democratic legitimacy more than three years into the union's worst ever crisis, new data shows.

After financial, currency and debt crises, wrenching budget and spending cuts, rich nations' bailouts of the poor, and surrenders of sovereign powers over policymaking to international technocrats, Euroscepticism is soaring to a degree that is likely to feed populist anti-EU politics and frustrate European leaders' efforts to arrest the collapse in support for their project.

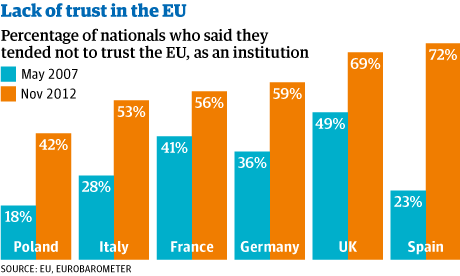

Figures from Eurobarometer, the EU's polling organisation, analysed by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), a thinktank, show a vertiginous decline in trust in the EU in countries such as Spain, Germany and Italy that are historically very pro-European.

The six countries surveyed – Germany, France, Britain, Italy, Spain, and Poland – are the EU's biggest, jointly making up more than two out of three EU citizens or around 350 million of the EU's 500 million population.

The findings, published exclusively in the Guardian in Britain and in collaboration with other leading newspapers in the other five countries, represent a nightmare for Europe's leaders, whether in the wealthy north or in the bailout-battered south, suggesting a much bigger crisis of political and democratic legitimacy.

"The damage is so deep that it does not matter whether you come from a creditor, debtor country, euro would-be member or the UK: everybody is worse off," said José Ignacio Torreblanca, head of the ECFR's Madrid office. "Citizens now think that their national democracy is being subverted by the way the euro crisis is conducted."

EU leaders are aware of the problem, utterly at odds over what to do about it, and have yet to come up with any coherent policy proposals addressing the mismatch between the pooling of economic and fiscal powers and the democratic mandate deemed necessary to underpin such radical policy shifts.

José Manuel Barroso, the European commission president, said on Tuesdaythis week the European "dream" was under threat from a "resurgence of populism and nationalism" across the EU. "At a time when so many Europeans are faced with unemployment, uncertainty and growing inequality, a sort of 'European fatigue' has set in, coupled with a lack of understanding. Who does what, who decides what, who controls whom and what? And where are we heading to?"

The most dramatic fall in faith in the EU has occurred in Spain, where the banking and housing market collapse, eurozone bailout and runaway unemployment have combined to produce 72% "tending not to trust" the EU, with only 20% "tending to trust".

The data compares trust and mistrust in the EU at the end of last year with levels in 2007, before the financial crisis, to reveal a precipitate fall in support for the EU of the kind that is common in Britain but is much more rarely seen on the continent.

In Spain, trust in the EU fell from 65% to 20% over the five-year period while mistrust soared to 72% from 23%.

In five of the six countries, including Britain, mistrust prevailed over trust by sizeable margins, whereas in 2007 – with the exception of the UK – the opposite was the case.

Five years ago, 56% of Germans "tended to trust" the EU, whereas 59% now "tend to mistrust". In France, mistrust has risen from 41% to 56%. In Italy, where public confidence in Europe has traditionally been higher than in the national political class, mistrust of the EU has almost doubled from 28% to 53%.

Even in Poland, which enthusiastically joined the EU less than a decade ago and is the single biggest beneficiary from the transfers of tens of billions of euros from Brussels, support has plummeted from 68% to 48%, although it remains the sole country surveyed where more people trust than mistrust the union.

In Britain, where Eurobarometer regularly finds majority Euroscepticism, the mistrust grew from 49% to 69%, the highest level with the exception of the extraordinary turnaround in Spain.

A separate, more detailed study published this week on the impact of the currency and debt crisis and the austerity policies that have followed also found steep falls across the EU in faith in democracy and national political elites.

The study for the Cabinet Office by the European Social Survey, linking university researchers across the EU, found that soaring unemployment, anxiety and insecurity had eroded faith in politics.

"Overall levels of political trust and satisfaction with democracy [declined] across much of Europe, but this varied markedly between countries. It was significant in Britain, Belgium, Denmark and Finland, particularly notable in France, Ireland, Slovenia and Spain, and reached truly alarming proportions in the case of Greece," it said.

The financial crisis "not only eroded the objective economic conditions of many citizens, but also created widespread anxiety about a country's future even among those who did not experience hardship directly".

Faced with this erosion of political support and the battering traditional politics is taking from populist newcomers such as Beppe Grillo's Five Star movement in Italy, policymakers appear at a loss.

On Monday, Barroso said the austerity policies being applied, mainly under pressure from Berlin, had reached the "limits of political and social acceptance" and were "unsustainable" in their current form. On Tuesday, though, the commission in Brussels sought to row back on his remarks.

Within the eurozone, the key response to the crisis, apart from bailouts, has been to embark on a systematic surrender of budgetary and fiscal powers from national governments and parliaments to Brussels, as well as having countries being bailed out overseen by a "troika" of technocrats and economists from the commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. These are "federalising" steps in a long process of eurozone integration that might see it transformed from a currency into a political union.

"The EU has hit home and is here to stay as a watchdog of budgets, labour markets, pensions etc. This is unprecedented, and risky," said Torreblanca. "Unless it is fixed, it will feed the vicious circle between anti-EU populism and technocracy which we are currently seeing operating."

Barroso argued strongly in two speeches this week that federalism was the only answer to Europe's crisis of finances and of confidence. The German chancellor, Angela Merkel, brushing off widespread fears of a new German "hegemony" in Europe and the eurozone, also said that governments had to give up much more power to Brussels.

"We still haven't found the answer to the question of whether we're actually now prepared to unite on common economic parameters inside the single currency area," she said in a Berlin debate with the Polish prime minister, Donald Tusk. "If we want to have a common currency, a common Europe, we have to be ready to give up our hard-won habits … That means we have to be prepared to accept that in the end Europe has the final word in certain things. Otherwise we can't keep on building this Europe … To an extent, we have to jump over our own shadows. I'm ready for that."

But Tusk delivered an unusually stark warning that German prescriptions could bring increasing nationalism and populism across the EU in a backlash that was already well under way.

"We can't escape this dilemma: how do you get a new model of sovereignty so that limited national sovereignty in the EU is not dominated by the biggest countries like Germany, for example," he said pointedly. "Under the surface, this fear will be everywhere: in Warsaw, in Athens, in Stockholm. It will be everywhere without exception."

Aart de Geus, head of the Bertelsmann Stiftung, a German thinktank, also warned that the drive to surrender more key national powers to Brussels would backfire. "Public support for the EU has been falling since 2007. So it is risky to go for federalism as it can cause a backlash and unleash greater populism."

No comments:

Post a Comment